Advice from the "Chess Educator of the Year"

By: Macauley Peterson

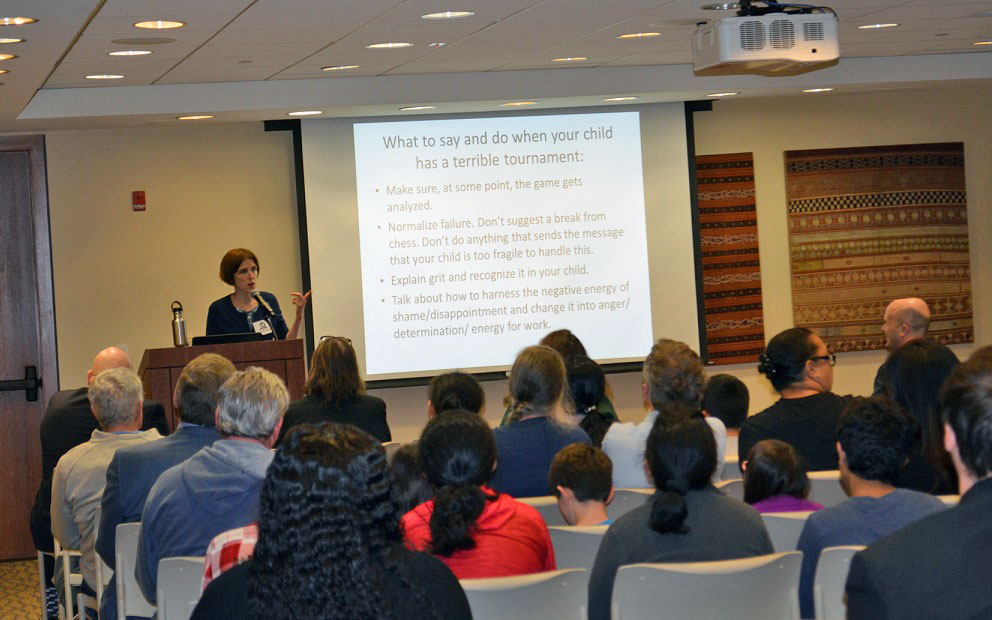

3/8/2019 – Elizabeth Spiegel is a public school chess teacher in Brooklyn, New York. Her program at IS 318 was the subject of the 2012 documentary film “Brooklyn Castle”. Recently she was given an award as “Chess Educator of the Year” by the University of Texas at Dallas, which has published her 55-minute talk that contains useful advice for parents and chess teachers gleaned from her 20 years of experience teaching chess. Video and highlights… | Photo: UT Dallas Eugene McDermott Library

Best practices for chess parents

Elizabeth Spiegel earned an AB in English from Columbia University and a Masters in English Education from City College in New York. She’s been a teacher at IS 318 since 1999.

In 2012, her middle school (Grade 6-8) team won the National High School Championship, a feat which had never been accomplished before or since. The team’s phenomenal record includes eight National Junior High Championships, four National Elementary Championships, and dozens of other national championships based on grade level.

Ellen Safley, Dean of McDermott Library, started off the presentation with introductory remarks and later awarded Spiegel a plaque as “UTD Chess Educator of the Year 2019”.

The full video is about an hour and we’ve summarised the key points and quotes below:

“One of the things I used to say to principals was, ‘standardized tests are so important, but what could possibly be better training for a standardized test than chess? You’re sitting there for 2-3 hours, you’re not allowed to talk, you have to solve a series of difficult problems on your own…that is a standardized test.’ When you say that to principals, and they make the connection, then it becomes much easier to sell the game itself.”

Chess is an effective teaching tool because it:

- reaches a level of complexity that other subjects don’t reach until later

“With chess kids are really pushed to do their own thinking and figure out their own problems and it’s really a whole level more difficult [than equivalent subjects in elementary school].”

- doesn’t require advanced verbal (or reading) skills, and so it reaches populations who are lacking them

- directly rewards thinking with winning, and kids take to it even if they are not generally excited about school

- is emotional, and motivating

“[Chess] is so hard and it’s so devastating emotionally when you lose and you just have to get over it right away and play the next round, and I feel that’s a really valuable character development lesson.”

- provides immediate, authentic and accessible feedback (like music and maths)

- teaches focus

- teaches grit

- teaches you to be honest and self-critical about your decisions

“Getting better at chess requires you to be incredibly honest with yourself and what you were thinking.”

Photo: UT Dallas Eugene McDermott Library

When a student is losing, figure out why they’re losing and target those weakness in particular — common ones are:

- blundering

- time trouble

- too many pawn moves

- moving one piece repeatedly

- making a mistake after lots of trades

- not knowing openings

- not making pawn breaks

- drifting after the opening (not having a plan)

- always trading

- not centralising the king in the endgame

- refusing to make ugly defensive moves

- not noticing an opponent’s threats

- always attacking the king in every game

- stopping analysis one more too early

- “wanting” (e.g. “I just felt like that was right” or “I really wanted to go there”)

“Blundering is a really common problem that kids have, and it’s also often thought of as a really shameful problem…it sickens them so much. But blundering is actually one of the easiest things to fix.”

Spiegel recommends deciding on our move, then looking at the position and then “blunderchecking” — asking specifically “if I go there, can they take me? If there was something wrong with that move, what would it be?” Making it a strong habit can significantly help at least a third of her students. “The idea that you’re getting kids to think about their own thinking process is so valuable.”

Four essential steps for chess improvement

- Play frequently

- Go over games (with your opponent, coach or an engine) and isolate specific takeaway lessons

- Acquire a manageable yet comprehensive opening repertoire

- Practice tactics

“Openings are really important in chess. Some people like to say that they’re not but it seems to me that they are incredibly important…Chess books are not written to be read [by kids] there’s no kid who’s going to read a 200-300 page book, but it’s pretty important to have a system of openings that works for you that you can also remember.”

How to be emotionally supportive

Frame your questions and conversation the right way, and don’t emphasise only winning and losing. “Tell me about your game.” “Are you feeling thoughtful, calm, focus, creative?” “What opening are you expecting?”

Introduce the idea of judging results by something other than your score. Set alternative goals like:

- avoiding time trouble

- sitting at the board and working hard

- predicting opponents’ moves so as not to be surprised

- coming up with a logical plan that fits the position

- playing creative or beautiful ideas

- accurately calculating a really long line

- avoiding simple (1-2 move) calculation mistakes

Ask your child to show you the game and explain it to you, even if you don’t play chess. Ask questions about the child’s thinking process: Tell me about that move. Why did you go there? What surprised you? Do you think your opponent played [this or that part of the game] well? What did you think was the best move here? What was your plan?

Listen as the coach goes over his or her game. You’ll get a window as to how your child makes decisions and gain insight into their thinking process. Coaches also tend to do a better job when other people are listening.

Look for a teacher who gives homework, has many students whose ratings have increased, asks for games in advance, reviews previously taught material, provides easy to understand opening reference sheets.

“I think showing whole games is a crazy way to teach. Whole games are so complicated, the idea that a child is going to extract a lesson from something that took Magnus Carlsen six hours to understand is ridiculous. Chess has to be broken down by the coach into chunks.”

Avoid teachers who always teach the same opening, or predominantly plays against your child during the lesson, or shows whole games or his own games, and talks most of the time instead of engaging with the child, asking questions and listening.

Photo: UT Dallas Eugene McDermott Library

What to say and do when your child has a terrible tournament

Make sure the game, at some point gets analysed, to learn from mistakes. Normalize failure — don’t send a message that your child is too fragile to handle this.

“The great thing about chess is that children will lose, and they will have terrible spells where they lose every game, and they are devastated, and they think ‘I’m stupid, I’m a failure’ and you get, as a parent to help them through it and it’s so great that it’s happening when they’re in elementary school or junior high school and not when they’re off at college and you can’t help them.”

Explain grit and recognise it in your child. A great lesson chess can teach is how to handle adversity and keep trying. Developing that habit when you’re young is extremely useful throughout life.

Talk about how to harness negative energy of failure, shame or disappointment. A child can learn how to take that same energy and use it to study and improve. Use that to fuel your work.